Welcome To Linux -- Distributions

Welcome back to “Welcome To Linux”, my user-friendly, non-technical guide to using Linux for personal computing! In the previous section of this guide, I introduced you to some of the basic information about the Linux operating system. In this post, we are doing to drill down a little further into a concept called distributions or “distros” for short.

What Are Distros?

I have a confession to make. Every time I referred to Linux in the previous Introduction post, I was actually referring to something called the Linux Kernel– a super basic, super modular piece of software that can be extended in any which way you want to build a custom computing system.

On it’s own the Linux Kernel is actually not a fully functioning operating system with apps, a desktop, or really much of anything you might recognize. Instead, the kernel it is just the framework used for building those tools out. If you were to go and download the Linux Kernel right now, it probably wouldn’t be of much use to you.

That’s where distributions come in.

To put it simply, Linux distributions or “distros” are pre-packed, pre-configured, pre-tested bundles of software that are capable of powering any number of computer configurations. At the center of each of these distributions is the Linux Kernel, acting as the common foundation for adding more and different bundles of software on top. This design makes it so that you can add just about anything else you want on top to make your own custom operating system.

Doing this by hand is famously rather difficult, but the good news is that we don’t have to do it by hand because plenty of other people have been hard at work making distros that are fun and easy to use. And there are a lot to choose from.

At last check, there are over 600 Linux distros in existence, some of which haven’t yet been discovered (note: I’m totally serious, some distros are private and nobody knows about them yet)!

Some distros are hand-made to solve specific technical problems, others are best suited for powering web servers or phones, but the distros we’re interested in are used for personal computing on a laptop or a desktop. Even then, not all distros are made equal.

Some appeal to more technical users who like to tinker, others are made for newcommers to Linux who expect their computer to look and behave a certain way, and still others are designed for people who want to use the newest software. As you might expect, we’re going to focus on the distros for newcomers to Linux.

All of the distros I am going to talk about in this post provide powerful and intuitive tools for managing your computer, come with the latest and greatest software available, and are backed by huge and dedicated communities that can offer support and guidance when you get lost. And, the best part, they all respect your privacy, are infinitely customizable to your exact needs, and are free to use.

On that note I want you to understand that, at a bare minimum, all of these Linux distros are capable of and recommend for:

- Gaming

- Office work

- Multimedia and graphics work

- Video calls and internet chats

- Web browsing

- Video and audio streaming

- Art and design

- etc.

Unless one distro is specifically well suited for one of these tasks, I won’t call attention to it for the sake of brevity. The good news is that no matter what you choose to use, you will be choosing from among some of the most popular and powerful distros out there today.

Don’t Commit Too Early

I also do want to emphasize one other important point. When taking a look at the distros I’m about to talk about, try not to skip over or commit to a specific distro simply based on how the desktop interface looks. Although this is an important consideration, be mindful of the fact that every part of a Linux distro can be customized or swapped out for something else. This includes the way the entire user interface looks or behaves, and what default apps your system comes with.

If a specific desktop screenshot doesn’t appeal to you, that’s OK: you can almost always install a version of that distro with a look and feel that does appeal to you (or modify it to your needs)! For right now, just focus on the big picture. Think about things like what kinds of software a distro supports, what its specific philosophies and goals are, and how those goals might align with your own. The more you consider these things early on, the easier it will be for you to be happy with your choice.

Then again, if you change your mind at a later time, that’s OK too! There is a proud tradition in Linux communities called “distrohopping”, where people jump around from one distro to another as their needs change or as their fancy moves them. It’s perfectly normal to commit to one distro now, try it out, and then switch to another one later on. Nearly everyone does it at one point or another, but rest assured, there is a distro out there that is just right for you.

The Distro List

Without any further ado, let’s take a look at some of the most user friendly Linux distros that you can download and start using today.

Zorin OS

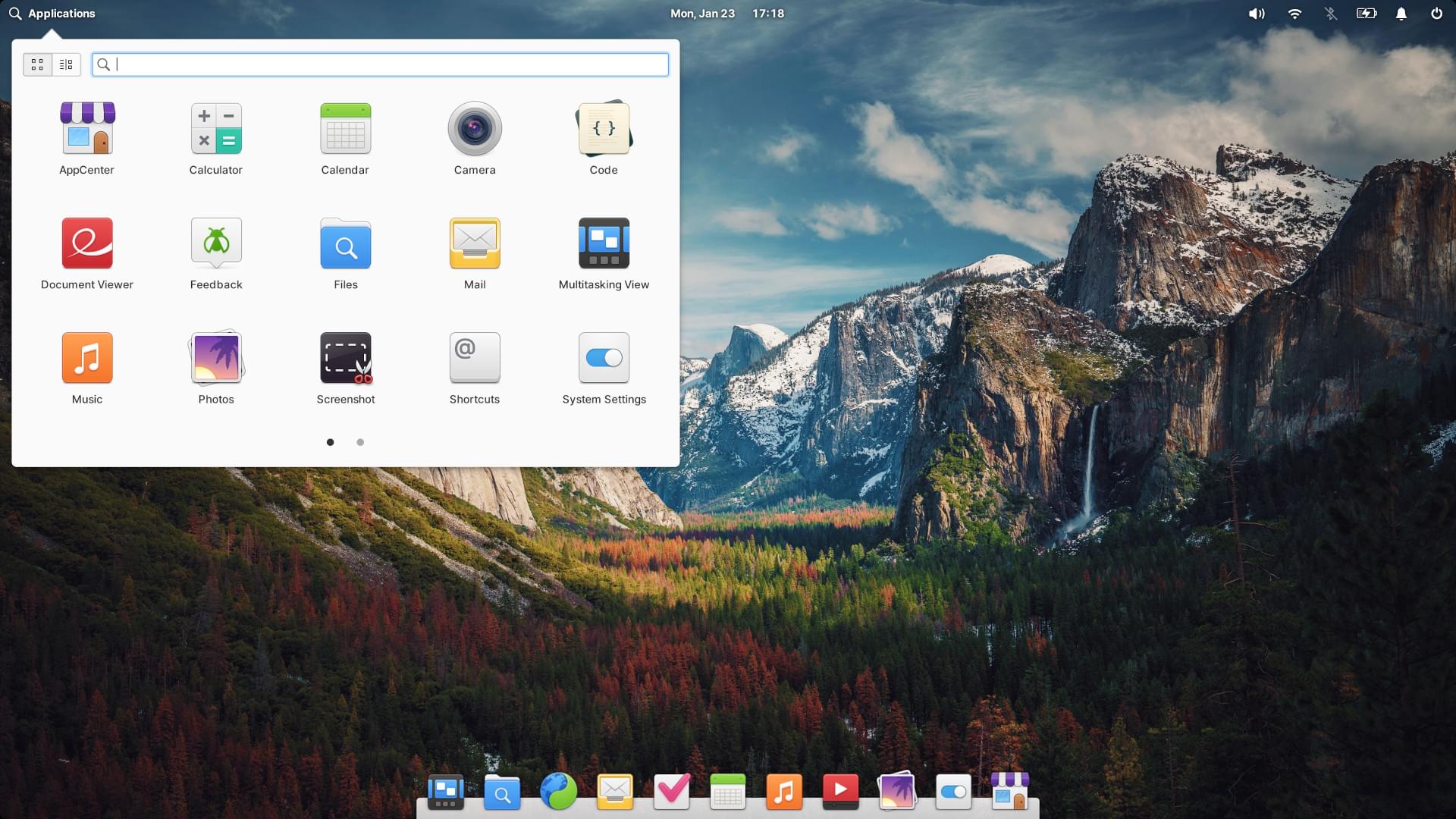

Zorin OS is a solid choice for users who are familiar with Microsoft Windows

Zorin OS is a solid choice for users who are familiar with Microsoft Windows

- Homepage: https://zorin.com/os/

- Downloads: https://zorin.com/os/download/

- Support: https://help.zorin.com/

- Discussion Boards: https://forum.zorin.com/

- Developed By: Zorin Group

Zorin OS is quite probably one of easiest distros to jump into if you are coming from Windows for three important reasons. First, the entire user interface has been designed from the ground up to look and behave like Windows. Second, a lot of the default applications were chosen or made to look like those that come with Windows. And third, Zorin actually comes with an application that helps your run your Windows applications, so you can just drop into a familiar workflow right out of the gate, no stress, no mess.

If you’re coming from the Mac OSX world, there is still a lot for you here since a lot of care has been placed making the user experience as intuitive and clean as possible.

Although the interface is styled like Windows by default (with a start menu on the bottom left and a system tray on the bottom right), there is nothing stopping you from making it look however you like (with a bottom dock or a top bar, for instance), and you can always swap out the system apps for something else that better suits your tastes down the road.

Do note that Zorin releases both free and non-free versions of its operating system. As far as I can tell, there is no huge difference between the two other than the fact that the paid version comes with more pre-installed software.

The free version will appeal to most users, especially if you’re just getting started. The non-free version, called “Zorin OS Pro” comes with a lot of bells and whistles that give you more software out of the box, but it is important to note that most (if not all) of that software is free to use and download from the Zorin app store. The difference is that the Pro version just sets it all up for you so you don’t have to.

Zorin will be a comfortable solution to people who want a plug-and-play, batteries included experience. If you want to just install an operating system and get going right away, this might be a great fit for you.

Elementary OS

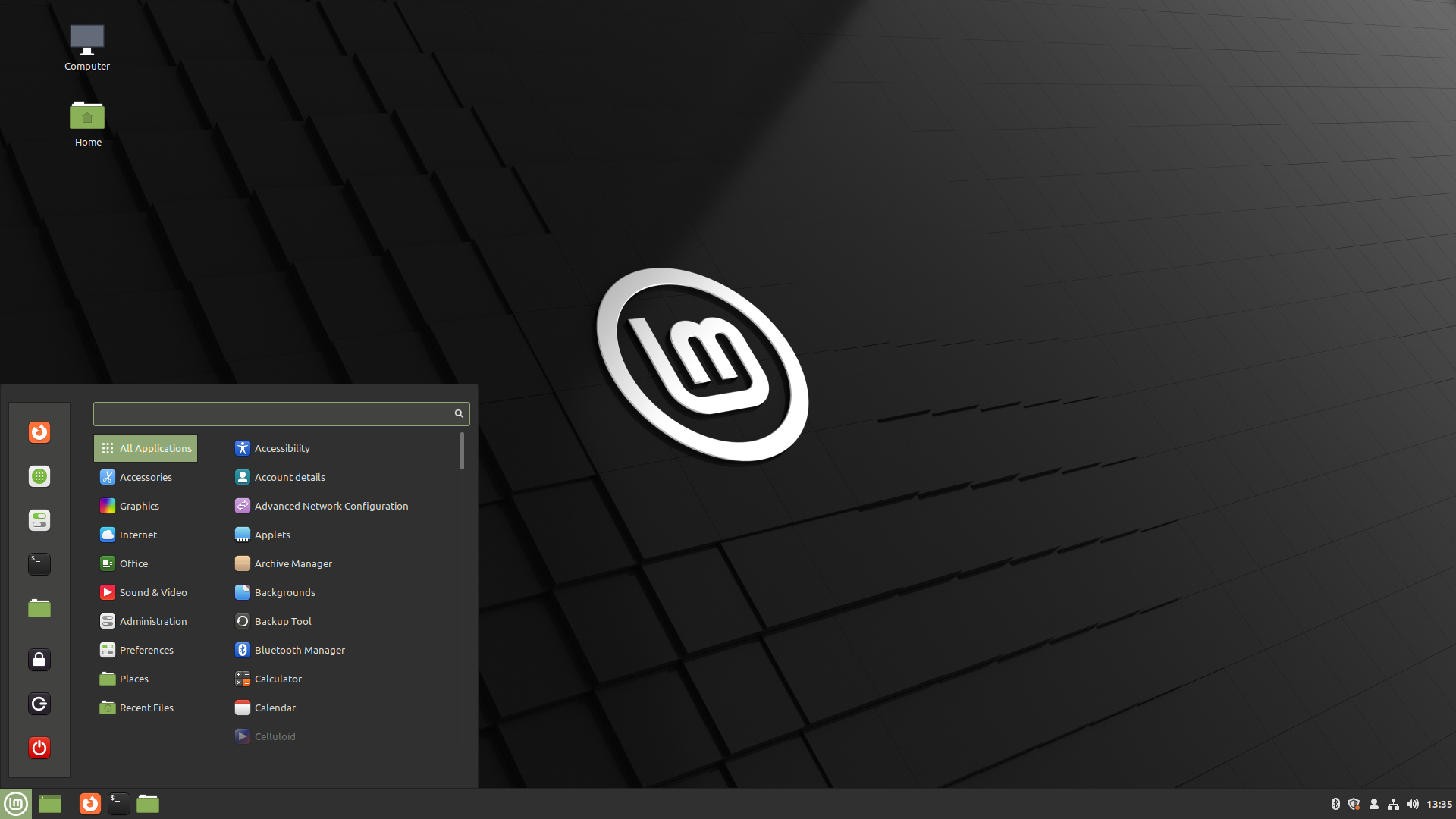

Elementary OS is a beautiful, functional, and clean Linux experience reminiscent of Mac OSX

Elementary OS is a beautiful, functional, and clean Linux experience reminiscent of Mac OSX

- Homepage: https://elementary.io/

- Downloads: There is a “Pay What You Can” button on the front page (linked above) that allows you declare your own price for download. $0 is a valid option.

- Support: https://elementary.io/support

- Developed By: elementary, Inc.

Elementary OS is without a doubt one of the most stylish distros out there, with ultra-clean looks reminiscent of Mac OSX. Elementary takes a more minimal and modern approach to their desktop interface.

There is a dock at the bottom of the screen, a top bar, a gorgeous wallpaper (usually of the sort you would expect from Apple, perhaps of a national park or a shot of Antelope Canyon), and that’s it. The interface intentionally omits desktop icons for a less cluttered look, but you can still manage all of your files from the integrated file browser.

If you’ve been reading this guide from the beginning, you may have noticed that a lot of the software we’ve talked about is totally free to use with no cost to the end user. That said, the cost to maintain, distribute, update, fix, and support a custom operating system is considerable, and the people who maintain these projects often work long hours solving difficult problems for free. Although people willingly volunteer their time and energy to contribute to open source operating systems, this is an admittedly difficult position to be in when you have real world bills to pay.

Elementary OS advertises itself as “[t]he thoughtful, capable, and ethical replacement for Windows and macOS” and it addresses the issues of developer compensation by implementing a unique pay-what-you-can model. Developers who decide to contribute to Elementary OS are given a share of the funds earned when a user pays for the distro.

Of course, you don’t have to pay anything to use or install Elementary OS, but the option is there if you’re feeling particularly generous. The upside of this is that the community of volunteer developers who make Elementary OS have an incentive to stay involved because they are getting paid to contribute to it.

This pay-what-you-can model is also reflected in Elementary’s beautiful app store (which other distros have subsequently baked into their software center offerings because it is remarkably elegant to look at). Elementary OS also has a partner program with app developers to help them get re-reimbursed for their work. If you are an app developer, you can actually partner with Elementary to list a suggested donation price alongside the download button for your app in the Elementary app store, that way you can get paid for you work that would otherwise go without compensation. Again, these prices are optional for the person downloading it, and you can opt to pay nothing if you wish.

The app store also includes a neat feature where if a given application you’re looking for is not in the app store (usually something like a commercial app that doesn’t make Linux releases– something like Zoom, Skype, or Slack), you can search against a secondary application store called Flathub. Flathub (and the apps on it, which are called “Flatpaks”) popped up a fairly recently in the history of Linux and were instrumental in unifying the diverse application ecosystem across Linux, Windows, and MacOS. Flathub is full of a mix of commercial and free applications that you wouldn’t traditionally find on Linux app stores, making it easier to jump into Linux and have familiar applications on hand without having to do anything extra.

Long time MacOS users will also appreciate the fact that Flatpak apps are self-contained, meaning that downloading, installing, and subsequently removing them has minimal impact on your file system. In other words, you won’t have to install 30-40 pieces of supporting software to install a Flatpak– it’s just plug and play, and when you’re done, uninstalling the app will remove all of the supporting software making it a very clean solution. By default, Elementary’s app store checks for updates on both Flatpaks and standard applications so you only need to visit one place and click one button to keep your whole system up to date. It’s a small detail, but it makes life a lot easier.

Elementary has also put a lot of thought into user experience and convenience, with unique features like the fact that pressing the “super” button (typically the “Windows” key or the Mac OS Command key) launches a handy keyboards shortcuts guide that helps you access some of the features of your system and make use of everything Elementary OS has to offer. This makes the user experience just a little more equivalent to the Mac OSX way of doing things where you have on super-powerful key for stringing together a bunch of handy system shortcuts.

When it comes to system settings, Elementary takes a very laid back approach. Out of the box, there is a Settings app that you can use to interact with various parts of your system. The settings themselves are intentionally sparse to help you focus on your work. This may not appeal to people like to tinker, but for the majority of people who just want a good looking desktop and a few toggles for system settings, it’s actually pretty relaxing. The rest of the fiddly stuff is actually pre-set by the operating system so you don’t have to worry about it. That said, there is no reason why you couldn’t just download a different settings app to change and manage more settings if you wanted to, but it isn’t required to get the most out of your system.

You’ll find familiar settings laid out in an Apple-like interface. There settings panes for printers, internet connections, firewalls, users, and appearance. There is even a settings panel for managing Wacom tablets for artsy folks and graphic designers– a rare and interesting consideration, but something that I am sure is very useful to someone out there.

Elementary OS will appeal to users who want a beautiful, clean, and minimal Apple-like computing system that still has the power to be shaped into whatever they want it to be. Elementary OS aims to “get out of the way” as much as possible to just let you focus on your work instead of setting up software or messing with your settings.

Linux Mint

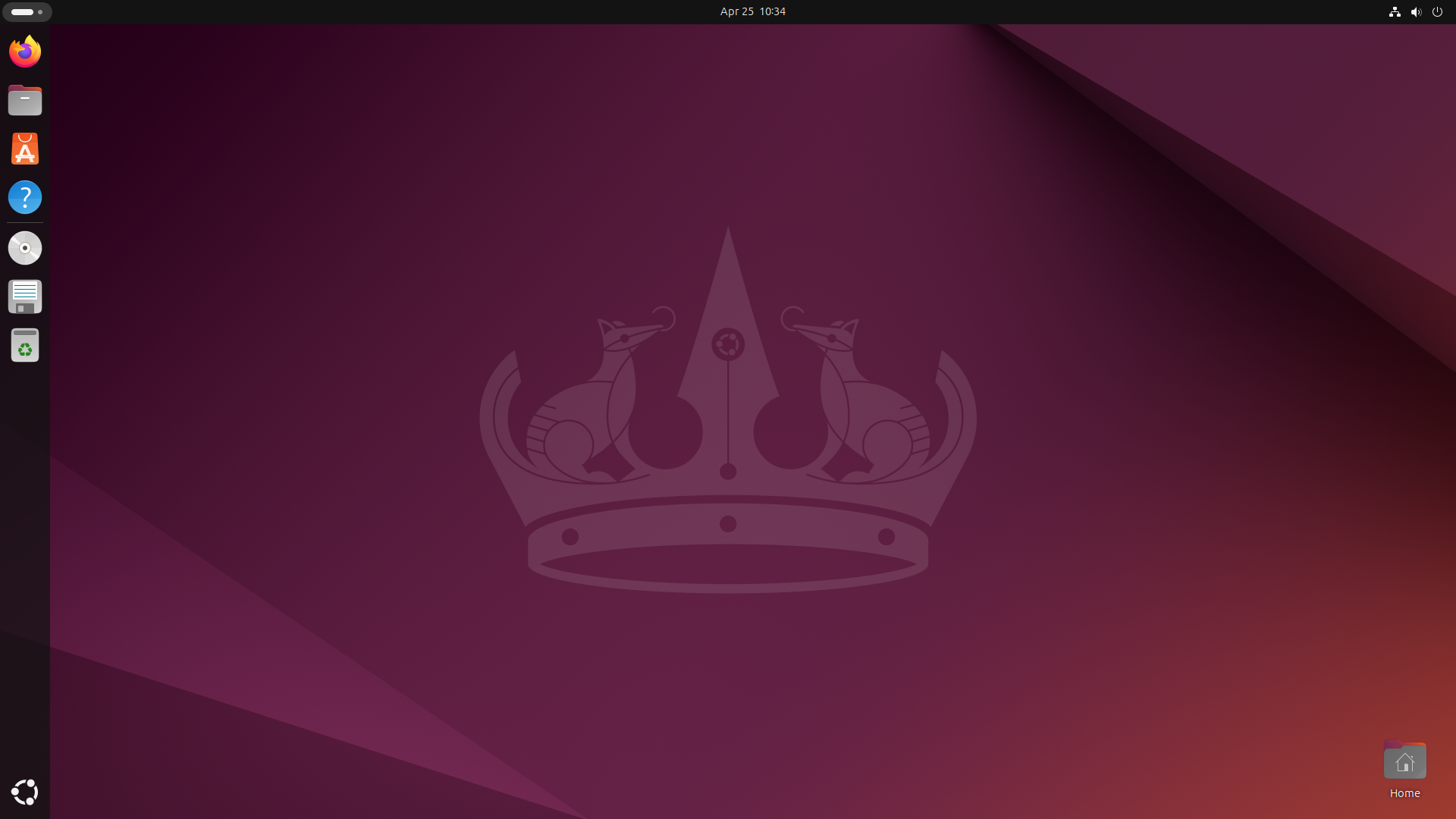

Linux Mint is a blend of ideas from both Windows and Mac OSX that still leaves you the freedom to experiment and explore.

Linux Mint is a blend of ideas from both Windows and Mac OSX that still leaves you the freedom to experiment and explore.

- Homepage: https://www.linuxmint.com/

- Downloads: https://www.linuxmint.com/download.php

- Discussion Boards: https://forums.linuxmint.com/

- Documentation: https://www.linuxmint.com/documentation.php

- Developed By: Clement Lefebvre and the Linux Mint community

Attentive readers may have noticed that, up til now, I have picked two distros that emulate existing operating systems based almost entirely off of form factor or design aesthetic. However, the Linux world is full of all sorts of distros that depart from the strictly traditional aesthetics and embrace their own path while retaining the ease-of-use of more familiar computer systems.

Linux Mint is one such distro that doesn’t go out of the way to exactly mimic Windows or Mac OS. Instead, it takes some notes from both and combines them into a unique offering that promises to give a solid, highly functional computing experience right out of the box. Although the basic layout leans a little more into the Windows-like aesthetic than usual, that’s about where the similarities stop.

Linux Mint doesn’t try all that much to be a Windows or Mac clone jam-packed with lookalike apps and workflows. Instead, Linux Mint follows the KISS principle, meaning Keep It Simple, Stupid. This translates to Linux Mint providing you with a minimal, functional Linux environment and the freedom install whatever you want afterwards. This experience will help you lean a little more fully into the Linux ecosystem while still allowing you to take baby steps along the way.

Like Elementary OS, Linux Mint also has Flatpak support enabled by default, making it easy to get any and every app you may need for your personal computer without creating a lot of clutter.

What makes Linux Mint a popular distro for new users is that it takes care of some of the more annoying parts of setting up a new operating system and still leaves you with the freedom to modify it however you like. Namely, you won’t have to spend a lot of time trying to reverse some of the design decisions that make other distros behave like a Windows or Mac OSX clone. Plus, the community behind Linux Mint is very strong and welcoming to newcommers since, after all, this entire distro is designed from the ground up with newcommers in mind.

Linux Mint is a very sensible option for people who still want a solid user experience that is intuitive and familiar, but still allows for the freedom to truly make it your own.

Ubuntu

Ubuntu is one of the most popular distros of all time, and it boasts bold looks you won’t find anywhere else.

Ubuntu is one of the most popular distros of all time, and it boasts bold looks you won’t find anywhere else.

- Homepage: https://ubuntu.com/

- Downloads: https://ubuntu.com/desktop

- Discussion Boards: https://ubuntuforums.org/ or https://askubuntu.com/

- Developed By: Canonical

I have another confession to make. So far, all of the distros I’ve talked about are actually Ubuntu under the hood with some modifications made to appeal to newcommers to Linux. Surprise!

So famous is Ubuntu’s legacy that it is by and far the most popular Linux distribution of all time, even for non-desktop usage. I’ve included it a little further down the page to ease readers into the notion that, quite often, Linux distros have a sort of parentage. Zorin, Elementary, and Linux Mint are just 3 distros out of many, many more that use Ubuntu as a base for building their own distro. This is a very common practice, and as you can tell, the kinds of communities and goals that the previous 3 distros were trying to achieve were all quite different from one another even though they’re all based off of Ubuntu at their core.

Funnily enough, Ubuntu is actually based off another distro called Debian which is famed for its rock-solid stability and vibrant user community. That said, Debian is often considered a bit more complicated to use out-of-the-box than your average distro, which is why user-friendly options like Ubuntu or Linux Mint popped up in the first place. It’s also why I’m not including Debian in this list– that’s because we can use distros based off of Ubuntu (and by extension, Debian) and take advantage of its powerful foundation without having to get into the weeds of Debian’s complicated installation and configuration process.

Since Ubuntu is the base off from which the last three distros were built, it takes a somewhat sparser approach to pre-installed applications. You won’t find any multimedia tools or gaming stores on your system when you first boot it up, but you can install them after the fact from the Ubuntu app store. The upside to this is that you have the freedom to only install the applications you need and nothing else. This has led to some folks saying that Ubuntu may not be the most user friendly option because there aren’t many familiar landmarks for folks coming from Mac OS or Windows.

Still, I include it here in this list because of two very important reasons.

The first being that Ubuntu has a massive community and a ton of support articles written just for it. Generally, if you plug “how to do such-and-such thing on Linux” in a search engine, you are almost always going to find instructions for how to do that thing on Ubuntu at the top of the list. That’s not a big deal if you plan on using the first three Ubuntu-based distros from this list because the instructions will be the same or very similar. However, it can be daunting if you use a wildly different operating system and you’re just looking for generic, non-Ubuntu instructions.

The second reason it is on this list is because Ubuntu is developed and managed by a company called Canonical. Canonical acts as the financial backer to Ubuntu’s ongoing development, and they offer high quality documentation and technical support (both paid and free) for Ubuntu. This sort of thing may appeal to companies who use Ubuntu in the workplace or users who want to make sure that there is a dedicated group of paid professionals they can turn to for help.

Between those two things, I think it is fair to recommend Ubuntu to hands-on sorts of people who want to dive head first into Linux and learn as much as they can. For those who like to play around with their setups and tinker with things, I think Ubuntu will suit those needs without making them feel too suffocated by the hyper-traditional layout and workflow of other operating systems.

In further parting from tradition, Ubuntu’s default user interface is markedly different than what you will find from those made by Apple or Microsoft. There is a top bar with a system tray for your clock, calendar, and notifications, and on the left hand side of the screen you will find a relative oddity in computing: a vertical dock.

This may seem like an unusual choice to those unfamiliar with the idea, but it’s something a lot of users with small monitors enjoy because it means they can still see all of their apps at a glance, but they do so without expending their ever-valuable vertical monitor space.

Some other elements of Ubuntu’s desktop design also depart from the familiar. It doesn’t take long to notice the bright orange, gray, purple, and reds making up the primary color pallet as opposed to the whites and cool blues that make up most user interfaces. Not everyone is a fan of the “Ubuntu look”, but you can say with certainty that it is striking and unique. If you open up your Ubuntu laptop at a coffee shop, don’t be surprised if you get onlookers or people asking you what kind of computer you’re using.

Not unlike Elementary OS and Linux Mint, Ubuntu also offers something in the way of self-contained apps called “Snaps”.

A while back both Snaps and Flatpaks went head-to-head as competing methods for packaging and distributing self-contained applications. The main difference between the two formats is that whereas Flatpaks are used by a lot of different distros, Snaps are sort of unique to Ubuntu.

One thing that may impact your decision to use Snaps over Flatpaks is that Ubuntu automatically takes care of updating Snaps without you having to take any action to do it yourself. You can disable automatic updates if you like, but it could be a nice piece of mind if you use Snaps pretty heavily. On the flipside, Snaps have a history of being a bit slower to launch than Flatpaks, but the folks at Ubuntu have been doing a lot of work to make up for this and now the difference in load time is relatively minor.

I bring all of these points up as a nod towards the fact that there are an abundance of alternatives in the Linux universe. If you don’t like one piece of software or a specific solution, you can almost always find another out there that works for you, and at the end of the day there is no universal commandment demanding you to use a solution you don’t like.

Part of what makes Ubuntu well loved among Linux users is the fact that there are Long Term Support releases of Ubuntu that are guaranteed to receive security updates and dedicated support for 5 years after their release date. These are usually called the “LTS” release, and is the one I would recommend for any user, regardless of how seasoned they are.

This 5 year release cycle is a big deal in the Linux world, especially for the distros that remix Ubuntu to make their own custom operating systems. You will often find that there is a 6-to-8 month delay between when Ubuntu makes a new LTS release and when descendants of Ubuntu (like the Zorins and Elementarys of the world) make their official releases.

Altogether, Ubuntu is a good choice if you want to use a distro that is pretending to be something else. It doesn’t hide the fact that it is different, and it makes a lot of decisions that make the Ubuntu workflow pretty unique among distros. In addition, the fact that Ubuntu is backed by a big company may bring some comfort to new users looking for a safe haven to start exploring Linux in earnest. You might have to do a little extra leg work to set up your system the way you like, but the resources to help you along that path are plentiful.

Fedora

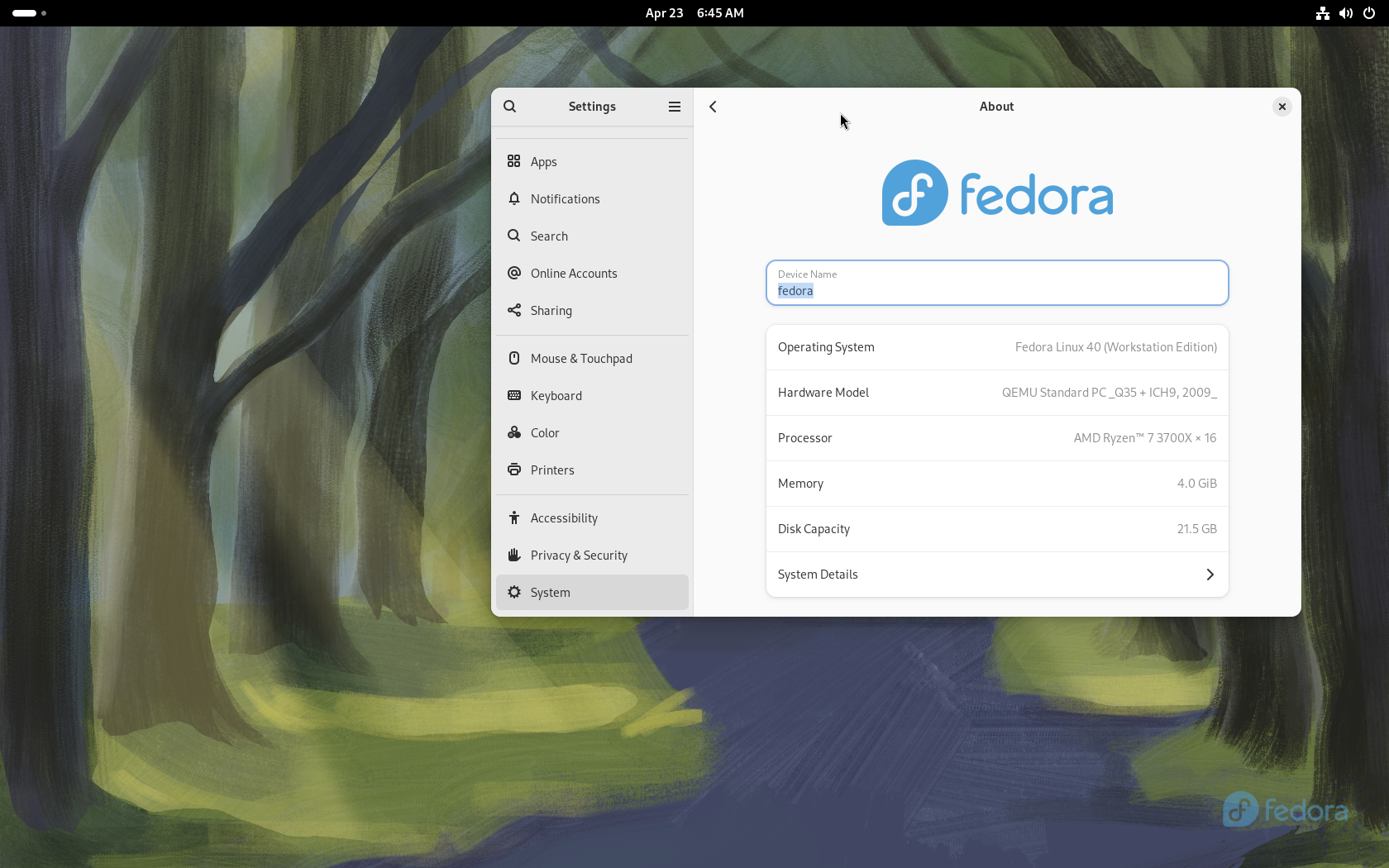

Fedora is a beautiful operating system with powerful system management tools to keep you system from breaking.

Fedora is a beautiful operating system with powerful system management tools to keep you system from breaking.

- Homepage:https://fedoraproject.org/

- Downloads: https://fedoraproject.org/workstation

- Discussion Boards: https://discussion.fedoraproject.org/

- Documentation: https://docs.fedoraproject.org/en-US/docs/

- Developed By: Red Hat Inc.

Fedora is yet another popular, easy to use distro that, unlike the previous contenders on this list, is not Ubuntu-based. I promise I don’t have any more surprises like that tucked up my sleeve. Instead, Fedora is based off of a system called Red Hat Enterprise Linux (or RHEL for short). RHEL is the flagship operating system developed by Red Hat Inc., a Durham based international software company that is among one of the most successful companies that develops and distributes Linux. RHEL was originally developed to appeal to businesses who wanted a commercial focused operating system to run their infrastructure, and it is still used for that purpose today.

Fedora benefits from being a descendant of RHEL in that it has access to a large repository of software, a dedicated userbase, and a parent company whose job it is to maintain Fedora, distribute documentation, and provide technical support, not unlike what Canonical does for Ubuntu.

Fedora has a 13 month release and support cycle, meaning that you are getting updates at a pretty frequent rate. Upgrading to new releases is also a breeze and can be done directly from the Fedora app store, meaning that you don’t have to do anything special to get access to the latest and greatest that Fedora has to offer.

What makes Fedora interesting is the fact that there are a few different flavors of the distro to choose from depending on how you want to manage your system. For instance, Fedora releases a traditional distro called Fedora Workstation which is the standard release. But they also release an entire series of so-called “Atomic Desktops”. These are desktop oriented operating systems that take a totally different approach to installing and updating software.

In the traditional way of running updates, you might update a piece of software and find that you unintentionally broke something else. The usual culprit is that you had programs on your computer that relied on an older version of the software you just upgraded. When that critical package gets removed or updated to a higher version, things that depended on it may start to break. This is a common problem across all operating systems and one that is kind of tricky to fix.

Fedora’s Atomic releases attempt to solve this problem by locking all of your system software to a version that they know works because it has been tested beforehand. When a new update is released, your entire system gets updated at once and a brand new, pre-tested environment gets installed in its place. If something goes wrong during the installation, the update simply won’t occur. This ensures that you always have a working computer. Plus, it gives you a chance to address what went wrong and fix it before you try updating again.

Another thing that the Atomic desktops boast is the ability to install all of your apps using Flatpak, a system which, incidentally, an engineer at Red Hat came up with in the first place. Taken together, these two systems make for a powerful, stable experience that is unlikely to break down in the future. One drawback, at least as of right now, is that not every application has been ported over to the Flatpak format yet, so you might end up missing out on some applications that you were used to.

Another is that if you wanted to break out of your comfort zone a little bit and try to do something that wasn’t strictly “the Atomic Desktop way of doing things” you might find yourself fighting against the system a little bit. The ideal user for this kind of system is a person who has limited computing needs and just wants their computer to work without a wayward update breaking their computer and causing a bunch of headaches. It’s a very set-and-forget kind of solution that has the potential to appeal to a lot of different people.

Going back to the more traditional Fedora Workspace release, you can still expect a high quality, stable experience with the added flexibility of being able to install whatever software you want at a moment’s notice.

In general, the Fedora experience is geared a bit more towards developers in the sense that it comes with development tools like a program that can emulate other operating systems. But even if you never touch those development tools, Fedora can be used for whatever you like and be a good fit for a variety of scenarios.

On the aesthetic side of things, the standard “Fedora look” is just plain gorgeous, full of curved edges, simple colors, and bold wallpapers. The desktop takes a highly modern approach with only a top bar to display system information. Like Elementary OS it hides desktop icons by default. The rest of your applications are arranged in a grid-style drawer that fades into view when you press the “super” key on your keyboard (this is usually the Windows key or the Mac OS Command key). Every part of the desktop is designed to be clutter free, elegant, and pleasant to look at, perhaps more reminiscent of a mobile or tablet-style computer.

OpenSUSE

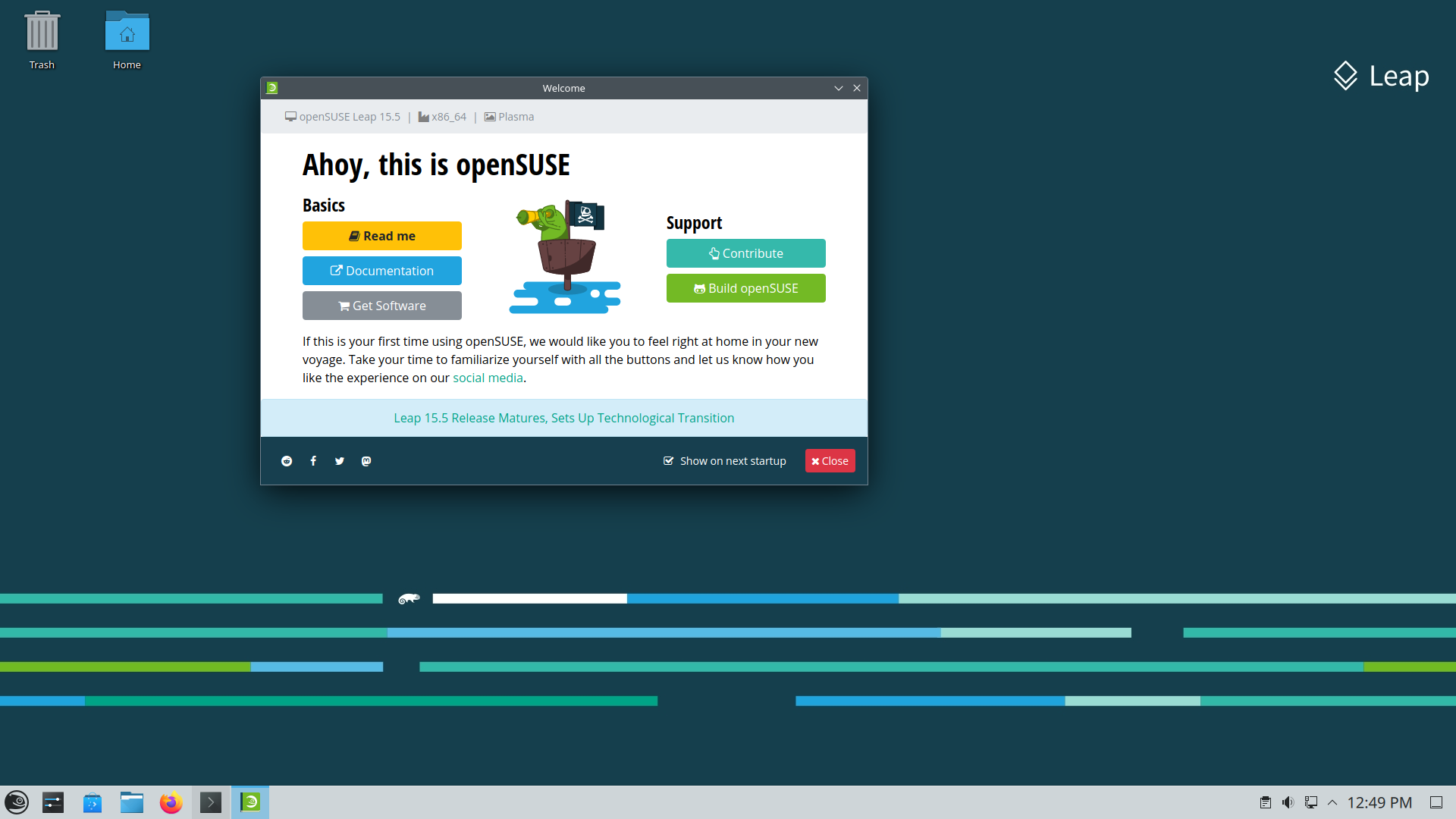

OpenSUSE offers some of the most powerful system management tools in the world while still being easy to use.

OpenSUSE offers some of the most powerful system management tools in the world while still being easy to use.

- Homepage: https://www.opensuse.org/

- Downloads: https://get.opensuse.org/desktop

- Discussion Boards: https://forums.opensuse.org/

- Documentation: https://doc.opensuse.org/

- Developed By: OpenSUSE Project

By no means should you take it as a sign that OpenSUSE, the last item in this list, is to be treated as an afterthought. By many accounts, OpenSUSE is considered one of the most underrated distros in Linux for reasons we’re about to discover.

As a broad overview, OpenSUSE is based off of another enterprise-grade operating system called SUSE Enterprise Linux, which is developed by the SUSE company headquartered in Luxembourg, Germany. OpenSUSE, by extension, is the general purpose operating system maintained by and for the desktop user community. Aside from the things you might expect by a distro that has corporate backing (including fantastic documentation, a lot of dedicated users, regular security updates, and more), OpenSUSE has some pretty amazing features that make it a strong choice for newcommers to Linux who want to squeeze every last bit of functionality out of their computer without having to read or memorize a bunch of dry technical material.

The first is the fact that OpenSUSE comes in two versions “Leap” and “Tumbleweed”. Leap is the name given to OpenSUSE’s regular release. It receives minor version updates every year, and new major releases every 3 to 4 years. In general, when a new major release is made available, you will want to install it as soon as you can to get the newest software and releases. When this happens, you will typically want to do a fresh installation to make sure your system is as stable as can be. This is a pretty typical recommendation regardless of which distro we’re talking about, and it’s something we’ll address more in the Support section of this guide (TBD).

On the other hand, re-installing your operating system fresh every couple of years can be a pain. So, for those who want a system that they only have to install once and it always stays up-to-date, OpenSUSE’s Tumbleweed version is the way to go. This is because Tumbleweed is something called a rolling release distro. By design, Tumbleweed is meant to only be installed one time and then kept up to date forever afterward. As long as you keep up with updates, you shouldn’t ever have to pay attention to when a new major release is coming out and wonder if your system is still compatible.

This is another way the “set-and-forget” approach is supported in Linux. Besides OpenSUSE Tumbleweed, there a lot of other distros that follow the rolling release model, but many of those distros require a bit more technical expertise and investment to make sure they stay stable over time. It isn’t unheard of in the rolling release world that a new update breaks something for a subset of users, and then they have to figure out how to fix it.

The good news with OpenSUSE Tumbleweed is that those updates undergo rigorous testing before they hit your system, so you can be sure that it will play nice with your existing setup. If you want to play it even safer, there is also another experimental version of OpenSUSE Tumbleweed called “Slowroll” which works just like Tumbleweed, but instead of receiving new updates right away Slowroll delays those updates by a month or so. This slight delay gives testers and users more time to ensure that the new updates work the way they’re supposed to.

Regardless of which version you choose, there are still lots of other reasons to consider OpenSUSE.

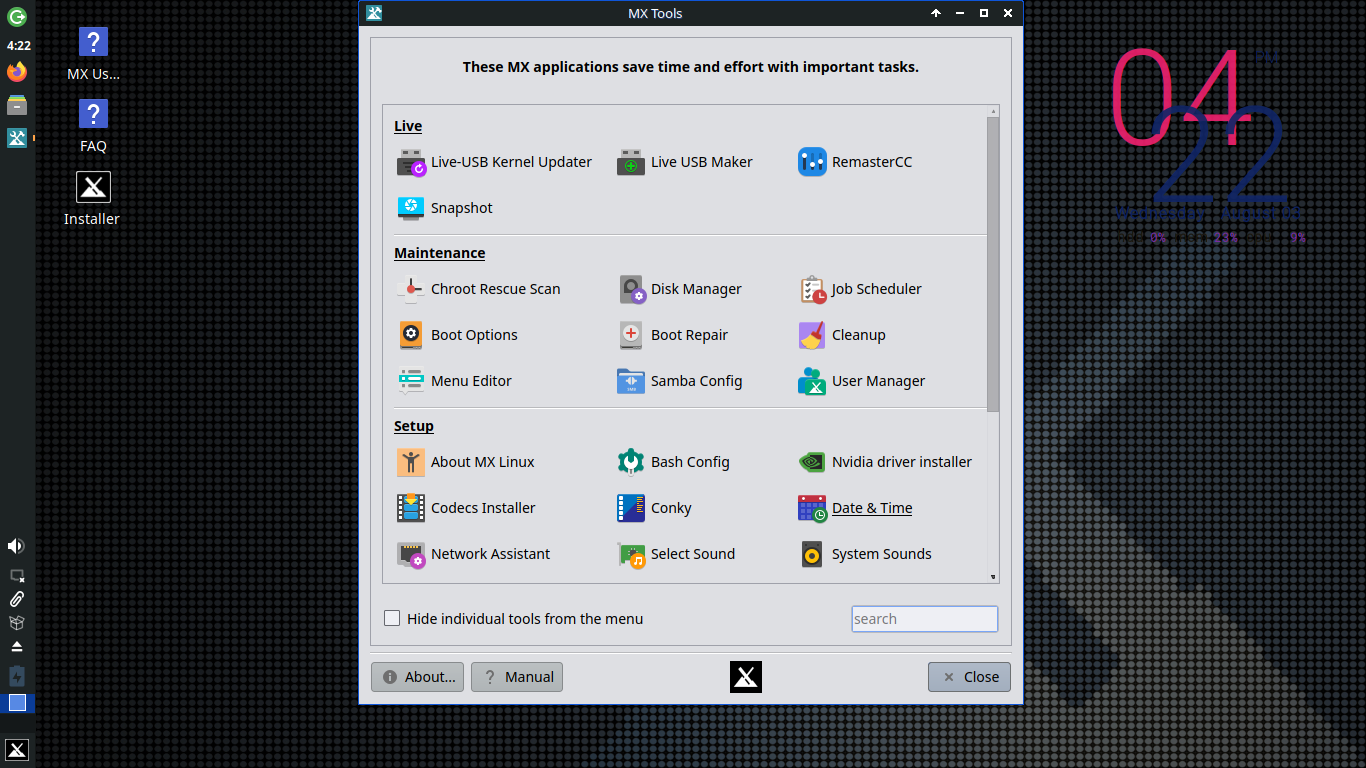

One of the most impressive things that comes with OpenSUSE is a tool called YaST, which stands for Yet another Setup Tool. In ye olden days, it was a popular practice for each distro to make and release its own take on a system management tool– a powerful, comprehensive, and labyrinthine list of system settings and tweaks that you could modify from one location without having to open up a terminal or fiddle with configuration files scattered all over you operating system.

These system management tools should not be mistaken for the regular old settings apps that come with other operating systems. YaST is on a whole different level altogether, and, interestingly, is the last of its kind from this forgotten era of system management. Dozens of tasks that you would usually have to accomplish by plugging commands into a terminal can be done visually in YaST, including installing and removing new software, setting up and managing unusual system boot sequences, exporting your system settings for use on other computers running OpenSUSE, tapping into new repositories of software not officially managed by OpenSUSE, setting up remote file sharing and firewalls, and so much more.

Some users find this YaST a tad too overwhelming for their personal needs, but the nice thing is that it is there if you ever need it.

Another interesting feature that comes bundled with OpenSUSE by default is file backups, but not in the way you might be thinking. All of the previous distros we’ve looked at can also take advantage of backups, even Time Machine-like incremental backups where you can bring your whole system back to a specific point in time. These usually rely on you having a large external hard drive just for storing these backups. However, what makes OpenSUSE’s approach to backups interesting is that you don’t need a separate application or even a separate hard drive in order to get the same experience.

That’s because OpenSUSE makes use of a special file system, that is a special way of organizing and managing your files, called BTRFS. What makes BTRFS special is that whenever a file is changed, you don’t overwrite that file, your system just makes a copy of it and the old version gets squirreled away somewhere else for safe keeping. If you ever need to recover the data on that old file it’s as easy as just opening up YaST on OpenSUSE and telling your system to roll that file back to the old version. If you want to go forwards in time, you can do that too.

All of this data is storied directly on your hard drive, meaning that you usually need to allocate a little bit more storage space for all of the backed up versions of your files, but you can just as easily erase old and unneeded copies of your data as needed (again, thanks to YaST). You can also manage rollbacks at a system wide scale, restoring your entire file system back to some point in the past, like right before you broke something.

Finally, I think it does bear mentioning that OpenSUSE is currently working on a new release called Aeon which is intended to be an atomic release like the ones made by Fedora. With it, you will get a similar level of safety and predictability during system upgrades because of the fact that the updates won’t apply if something about them would break your system. Aeon is still in testing as of the time of writing this, so I wouldn’t recommend using it at this time, but it may be worth keeping an eye on if the idea of an always-guaranteed-to-work system appeals to you.

Outside of all of the cool features that OpenSUSE comes with, you can also expect this distro to come with a large number of pre-installed applications including games and gaming platforms, an office suite, system utilities like a webcam and torrenting tools, and a couple of other things that make the desktop feel complete from the moment you boot it up.

Other Options, In Brief

I don’t want to throw too much at you at this point in time, but there are a few other distros you might take a look at if none of the ones here caught your eye for some reason. I left these out of the primary list because they were a little too similar to other distros to make a direct comparison and speak on at length, but they still offer a good user experience and are good choices for certain people.

Pop!_OS

Pop OS is a popular choice for makers and heavy graphical work, or just anyone who wants a simple, functional operating system.

Pop OS is a popular choice for makers and heavy graphical work, or just anyone who wants a simple, functional operating system.

- Homepage: https://pop.system76.com/

Based off of Ubuntu and developed by Linux computer manufacturer System 76, this operating system is designed from the ground up to be as useful to newcommers as it is to seasoned professionals. It comes pre-installed on all of the computers made by System 76 and is generally intended to be a person’s very first Linux experience. What people like about this distro is that it lowers the learning curve that comes with Linux by a great deal and provides a lot of ergonomic improvements that you would typically have to set up yourself like window tiling and workspace management tools.

All of the choices that the team at System 76 decided on make the whole experience feel very clean and well considered. This distro includes a lot of hand picked software and a very intuitive workflow that makes it ideal for both tinkerers and casual users. It also has earned a reputation for being a good distro for intense graphical jobs like gaming, CAD modeling, 3D modeling and 3D printing, and graphic design. So if you are a tinkerer, gamer, STEM geek, or artist by trade this may be the ideal choice for you.

MX Linux

MX Linux is a popular distro that offers a traditional Linux experience and is more suited for technical users who want to learn Linux from the ground up.

MX Linux is a popular distro that offers a traditional Linux experience and is more suited for technical users who want to learn Linux from the ground up.

- Homepage: https://mxlinux.org/

This is admittedly a bit of a rare recommendation to make to newcommers, but I think this distro is worth considering because of its recent meteoric rise in popularity which, at least to me, must mean that they’re doing something right. MX Linux is based off of Debian which makes it a sibling to Ubuntu, not a descendant of it. What makes MX Linux a solid choice for beginners is that it offers a simple, no-nonsense experience more heavily steeped in Linux design principles than other distros on this list.

If you consider yourself a more advanced or adventurous user who wants to see what Linux is all about, this might be the way to get your hands dirty and learn a lot in the process. I would roundly consider this a more advanced option, however, so be forewarned that you may need to learn your way around a terminal and the Linux file system. If that’ doesn’t scare you, then you’ll probably be OK. MX Linux also works fantastic on older computers, so it may be an ideal candidate to put on that old laptop you have laying around.

This is also a community powered distro like Elementary OS, Zorin OS, and Linux Mint, meaning that there isn’t a company backing it financially. That may not be a drawback, however, when you consider that the community behind making this distro is really quite large and very dedicated. Some time back, two other Linux communities from defunct distros merged together to help make MX Linux by melding their interests together and pooling their resources. If you were looking for an opportunity to get involved in the Linux community, this may be a good place to start.

Next Steps

I would urge you at this point to explore, read up on the distros that caught your interest and start considering which community feels the most inviting, interesting, or comfortable to you.

In the next post, I am going to discuss another Linux concept called “Desktop Environments”. This post will talk about the fact that, in Linux, if you don’t like the way a certain distro looks or behaves, you can just as easily swap out the entire user interface for something else that does. Or, just as easily, you can install two different desktop environments, and switch between them whenever you want.

This is an extremely powerful feature of Linux that takes some getting used to, so it is worth talking about it and exploring some of the options you have at your disposal.

On the other hand, if you were happy with the screenshots featured in this article, you don’t need to learn about desktop environments at all. Just follow the download link under your distro of choice and it will direct you to the place you want to go.

Otherwise, click here to learn about Desktop Environments (TBD).