Joust

Demo Video

A Multi-Player Chess Game Designed For Mobile

Some years ago, I built a single-player chess game called Rudrata based around the knight’s tour. If you’re not familiar with the concept, the object of the game is to visit every square on a chessboard using only a knight. More recently, I wondered what it would be like if there were two knights on the board: one white and one black.

The concept of this game came about while I was learning about building native applications using Ionic, a framework that allows developers to create iOS and Android apps using web technologies. I was also curious about trying out a cloud database called Firebase, specifically something called a real-time database that would allow two players to “listen” for each other’s moves and re-render the game interface accordingly.

What I ended up creating was this game.

Talking Points

- Powered by Ionic, a platform for building native iOS and Android applications

- Uses Firebase, a real-time database service that allows multiple users to subscribe to database updates as they happen

- Written in TypeScript using the React frontend

Game Play Demo

The Concept

I thought it would be interesting to dual against another player using the knight’s tour problem. I wanted to make a game where each player visited squares on the chessboard and reduced the playable space with every turn. The game would therefore be over if a player got trapped on the chessboard and was unable to make any more moves. Likewise, the game would also be over if a player was able to capture their opponent’s piece.

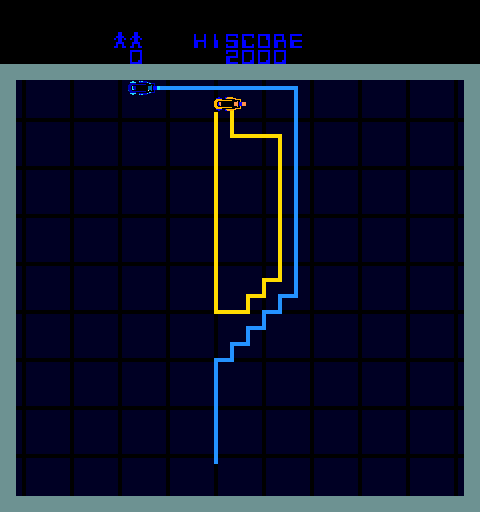

After a while, I realized that this would be a game sort of like Tron, where players on hyper futuristic motorbikes are trying to “box in” opposing players with the solid neon jet-trails emitted by their bike.

A screenshot of the original Tron arcade game. The orange player has locked themselves into a losing position and is about to collide with the blue player’s light trail.

A screenshot of the original Tron arcade game. The orange player has locked themselves into a losing position and is about to collide with the blue player’s light trail.

Firebase & Real-Time Databases

In order to build this app, I had to design a matchmaking system that could pair up players from a queue and then mediate the game as each player took turns moving around the board.

The primary way to accomplish this was by using a web technology called the WebSocket protocol, a sort of cousin to the more well-known Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

Traditionally, HTTP is the go-to protocol for facilitating web-based communication because it breaks a single page request up into bite-sized chunks, which allows for easier delivery. Every image, every file, and the page markup itself are delivered one-at-a-time in what is sometimes called a “cascade” or a “waterfall” of parceled data. This strategy makes HTTP ideal for delivering complicated web pages with lots of little bits and pieces.

However, what HTTP gains in logistical advantages, it pays for in performance and bureaucracy. Every HTTP request requires re-establishing a connection between the client and host servers to some degree. In most cases, this means that for every parcel on a page the client must re-introduce itself to the host sever, ask for what it wants, wait for the host process their request, and then receive the response.

This is a one way relationship: the waterfall of data can only be delivered when the client asks for it, and even then only after it has made a successful re-introduction to the host.

But what if you need it to work the other way around? What if you want the host server to deliver information to the client at seemingly random times, as in the case of a push notification? Or what if you want two clients to be able to communicate with each other, like in a multi-player game?

Those are the kinds of problems WebSockets were built to fix. In short, a WebSocket is a persistent connection between a client and a host where either party can send data to the other at any time. In this kind of setup, the lines between client and host are blurred because both sides can “listen” for data coming from the other and react accordingly. It isn’t a great way to transport web pages, but it is really handy for sending JSON data back and forth.

Say for instance you’re playing a multi player game like Joust, and you play your turn. Now you’re just waiting for your opponent to do the same. In order to know when your opponent made a move and what that move was, both of you would need to be hooked up via WebSockets to the same host server, listening and responding to each other’s moves. In this scenario, the host is acting as a sort of mediator or referee, deciding which moves are legal, which are not, and alerting a player that their opponent just made a move.

This was the setup I decided I needed for my application, and the easiest way I found to make it work was by using a software platform called Firebase. Firebase is a former Google company that creates a number of cloud-based data-management tools, one of which is a real-time database.

A real-time database, as you might expect, is a database that uses WebSockets. It enables clients to “subscribe” to a piece of data in the cloud. Whenever that data changes, all subscribed clients will be alerted. From there, the client application can react accordingly and change its behavior or interface.

Integrating Firebase with an app is somewhat complicated because, beyond being a WebSocket database, it is also cloud hosted. Firebase has a interesting “pay what you use” model where they only charge you once you app begins to get a lot of traffic. However, seeing as how I wanted to be able to build and test this application myself, I decided to host the database on my local machine. Firebase provides a free Java-powered tool for emulating their databases, so I used that to develop the app.

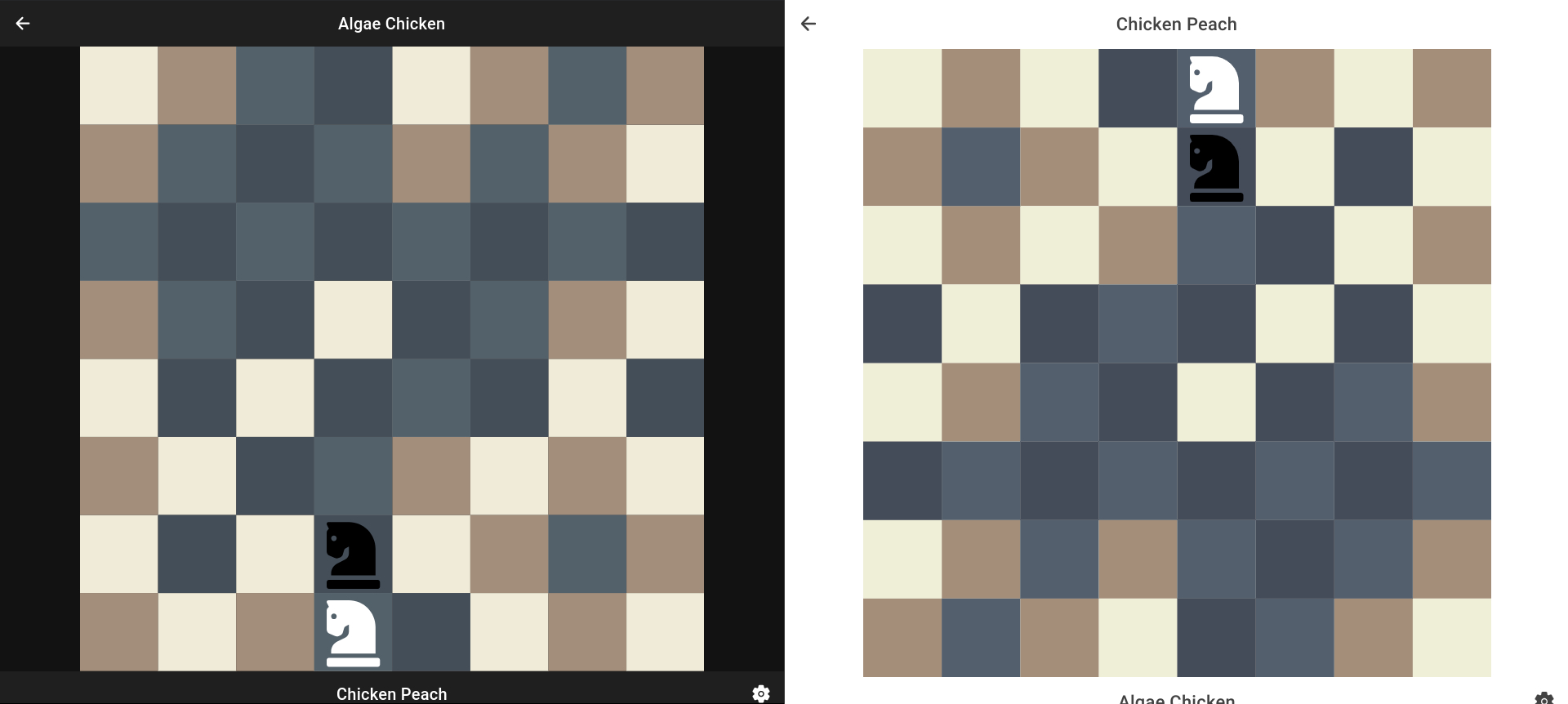

Two players in a match of Joust, shown side-by-side in different browser windows. The chessboard is flipped for each player in order to mimic the effect of sitting on opposite sides of a chessboard.

Two players in a match of Joust, shown side-by-side in different browser windows. The chessboard is flipped for each player in order to mimic the effect of sitting on opposite sides of a chessboard.

Ionic

I wanted this game to be playable on either a mobile phone or a web browser. In order to accomplish this, I used a framework called Ionic. Ionic is a bundle of open source software that enables developers to build iOS, Android, and desktop applications using web tools like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

It handles some of the bigger-picture concerns in application building that systems like React alone can’t quite do on their own. For instance, Ionic integrates with platform-specific libraries like Cordova so that it can communicate directly to the device that is running the app. That makes it so developers can use JavaScript to, say, turn on and off a phone’s flashlight whenever the user clicks a button.

Although those features were handy, all I needed was the reassurance that the app I built would integrate easily into a mobile environment, and Ionic was a fantastic candidate for building this application.

React & Typescript

Jumping into the more nitty-gritty aspects of the system, I built this application using React and TypeScript. Seeing as how this application was pretty complicated, I was happy to use a strongly-typed language to define application logic, write custom object types, and handle some of the more complicated data transactions.

Using TypeScript also had the advantage of being able to define abstract types and interfaces that I could use on both the client and the host sides at the same time. Going back to WebSockets, I needed the host to have some kind of built-in validation system for making sure the data it was receiving was in the proper format.

Each move the player made on the chessboard, for instance, had to transmit information about what piece moved where and at what time. Instead of writing my own logic to parse and validate this data, TypeScript made it so I could write one abstract “Move” type interface, define the data I expected to see, and then just use that single “Move” definition to inform the entire transaction from client to host.